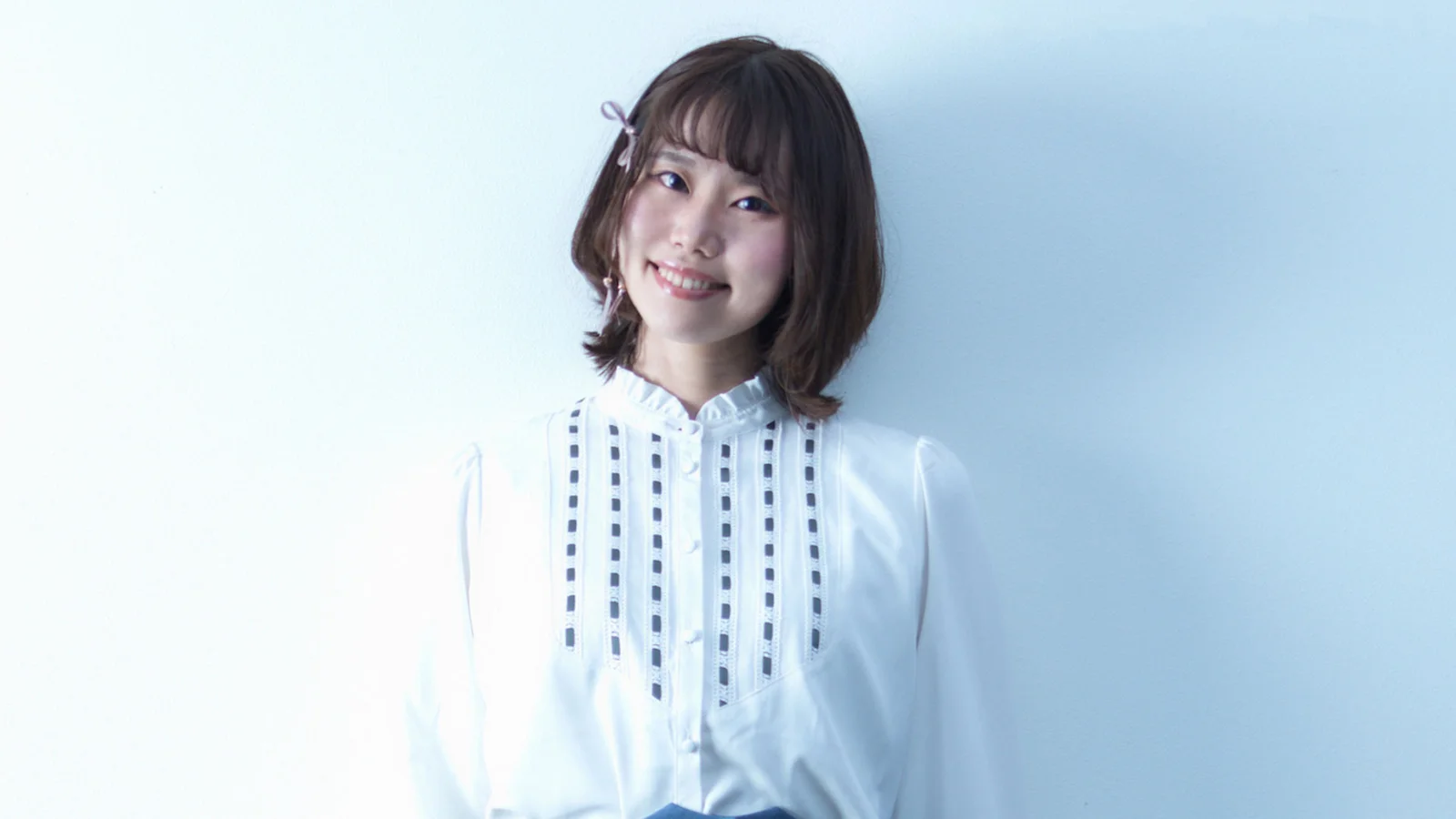

Chasing Lynxes and Sunrises: Life as a Wildlife Photographer with Alexandra Surkova

Alexandra Surkova

Once on track for journalism and diplomacy, Alexandra Surkova instead found her true calling in the wild, camera in hand. Her photography reflects both the unpredictability of nature and her commitment to making every image pulse with life.

Thank you so much! Honestly, I never thought I’d end up as a wildlife photographer. I studied journalism and diplomacy—so technically I was supposed to wear suits, not camouflage. But life had other plans.

What inspired me? A very unexpected gift. A stranger who followed me on Instagram liked the street photos I was taking with my very first camera, and instead of sending a postcard, he sent me a Sony 200–600mm lens. That was the turning point.

My first wildlife shots were terrible—I’m pretty sure even the squirrels looked embarrassed for me. But little by little, I got hooked. What started as “let’s see if I can take a nice picture” turned into “let’s survive +50ºC just in case a lynx might show up, or not.”

Since then, the journey has been full of missed shots, unforgettable encounters, and many moments—especially at 4 a.m. when the alarm goes off—when I thought: “Why am I doing this to myself?” But then, the animal appears, you press the shutter, and you remember exactly why.

So yes, it started as curiosity, became an obsession, and now it’s a lifestyle (one that includes permanently muddy shoes and way too many hard drives).

One of the winning photos is of a lynx cub surrounded by bees—curiosity meeting curiosity. The little one was completely fascinated, and instead of looking like a future predator, it looked more like a clumsy apprentice beekeeper.

That’s what I love about wildlife photography: you can wait for hours, even days, imagining a powerful, majestic scene, and then nature gives you something far more surprising, tender, and unique.

Winning with this photo makes me feel grateful—not only for that fleeting moment but for the entire unpredictable journey that led to it. Every 4 a.m. alarm, every missed shot, every “what am I doing with my life?” thought suddenly feels justified when the animal decides to surprise you.

For me, this award is a reminder that patience pays off, and that sometimes, the best stories in nature are also the funniest ones.

It’s pure intuition. I submit the photos that move me first, because if they don’t make me feel something, why would they move anyone else?

I bought my first camera six years ago for street photography. I was obsessed with this idea: if I take just one photo a day, maybe I can reconstruct my entire life. With that obsession, I got my first camera, started shooting, and then COVID arrived.

So there I was—a street photographer, without a street. I started travelling through empty countries, turning the camera on myself, and even placing my family in the frame just to keep the photos alive.

And then came that unexpected gift I mentioned before—the lens that completely changed my path. It made me leave behind a 15-year career in journalism and start everything from scratch as a wildlife photographer. Probably the best plot twist my life has ever had.

Wildlife photography. I love it because it’s the only genre where “waiting 10 hours and coming back with nothing” is considered completely normal, and somehow, still addictive. And unlike people, animals never complain about how they look in the photo.

But if we’re speaking seriously, every encounter with an animal makes me feel incredibly alive and grateful. To witness such limitless beauty in the wild is a privilege that never loses its magic.

My go-to setup is the Sony A1 II with prime lenses. The 300mm f/2.8 is my favourite because of its incredible balance of sharpness and lightness—after long hours in the field, that makes all the difference. It feels fast, intimate, and almost effortless to carry compared to bigger glass.

That said, I also adore the 600mm for its unparalleled bokeh. It can turn a messy background into pure magic, and sometimes I think the lens has more artistic vision than I do.

Why does this setup work best? Because in wildlife, every fraction of a second matters, and I need equipment that reacts instantly. My favourite feature of the A1 II is its fast autofocus—it lets me work without relying on bursts, capturing the exact moment I want with precision.

What I’d love people to feel is exactly what I felt in the moment I pressed the shutter. I think that’s the most difficult thing in photography—to make an image speak with the same intensity as the living being in front of you.

If my photo can carry even a fraction of the heartbeat, the silence, or the electricity of that encounter, then I know it worked.

With the lynx photo, honestly, the moment didn’t depend so much on me—it was nature’s gift. You don’t see a lynx cub interacting with insects in perfect sunset light every day. My real “merit” there was choosing to follow that cub with my camera, even though five other individuals were playing around at the same time, and then pressing the shutter at the exact second, without using bursts.

The elephant photo, on the other hand, makes me especially proud because it was all about anticipation. That day on safari, I only had a 400mm with me. When we spotted the elephant, it was already way too close to fit in the frame.

Then I noticed a tree in its path and thought I could take a risk: if it passed behind, it might look like the elephant was playing hide-and-seek, since the bark and the skin had such a similar texture and colour. I pre-focused on the tree, waited, and the elephant passed exactly where I had imagined.

That shot was born out of a technical limitation that forced me to be creative—and not miss the moment.

Africa, for me, is a continent of limitless inspiration. It allows me to experience the full spectrum of emotions in such a short period of time—it’s like being plugged into pure adrenaline.

But right now, what excites me most isn’t just photographing animals as the final goal. It’s being part of conservation projects that can truly help protect this world around us. For me, that feels like the most meaningful way to use photography—to create images that inspire, but also contribute to something bigger than myself.

I would say my father first, because he introduced me to photography. But my biggest ongoing influence is nature itself. Every animal, every encounter, pushes me to see differently. They are the real mentors—you just have to be patient enough to listen.

My message would be: don’t overthink it—just submit. The worst thing that can happen is that nothing changes. The best thing? Your work gets seen, your confidence grows, and sometimes you even surprise yourself.

As for advice, I’d say: don’t try to guess what the judges want. Choose the photos that move you first. If an image still makes your heart race every time you look at it, chances are it has the power to move others, too.

And remember—awards are not just about winning. They’re about learning how to edit your own work, to see your photography from the outside, and to push yourself a little further.

For me personally, the real motivation isn’t winning prizes—it’s the hope that more people might see the beauty around us. We never know who is looking at our images. Sometimes it may touch just one person, but that one person could be the one who changes everything.

And most importantly, have fun, because if you don’t enjoy the journey, no trophy will make it worth it.

Start by photographing what makes your heart beat faster. Forget trends, forget likes. If you fall in love with what you’re shooting, the rest will follow.

For me, editing is just as important as taking the photo—because that’s where your personality, your vision, and your way of telling the story truly appear.

Think of it like food: you don’t go to a restaurant for raw tomatoes, you go for the flavour that a specific chef creates. Photography is the same. It’s not about the raw file, but the finished work—how you saw the scene, how you chose to tell it.

Even if ten photographers stand in front of the same animal, none of the photos will ever be identical. First, because we all see differently. And second, because we all edit differently. That’s the beauty—the magic—of photography.

I believe showing the truth is a revolutionary act.

AI can create perfect images—even scenes that move you—but they will always lack one thing: they never actually happened. A real photo connects you to the cold air, the smell of earth, the silence broken by a roar. It carries the emotion of a fleeting moment that existed only once.

Yes, it’s easier to ask a machine for a snow leopard than to freeze at –30°C and still come home with nothing. But that risk of failure is part of the truth—and what makes the reward unforgettable when it finally happens.

AI can manufacture beauty. But beauty without life doesn’t change the world. The images that do are the ones born of real encounters, real emotions, real stories. In a world where fake often looks more real than authentic, showing reality is the most radical thing we can do. It may be art, but it is not photography.

Honestly, any animal that makes me feel small in front of its presence. The species may change—the lynx, the gorilla, the elephant—but what I’m chasing is always the same: that feeling of awe when you realize you’re part of something much bigger.

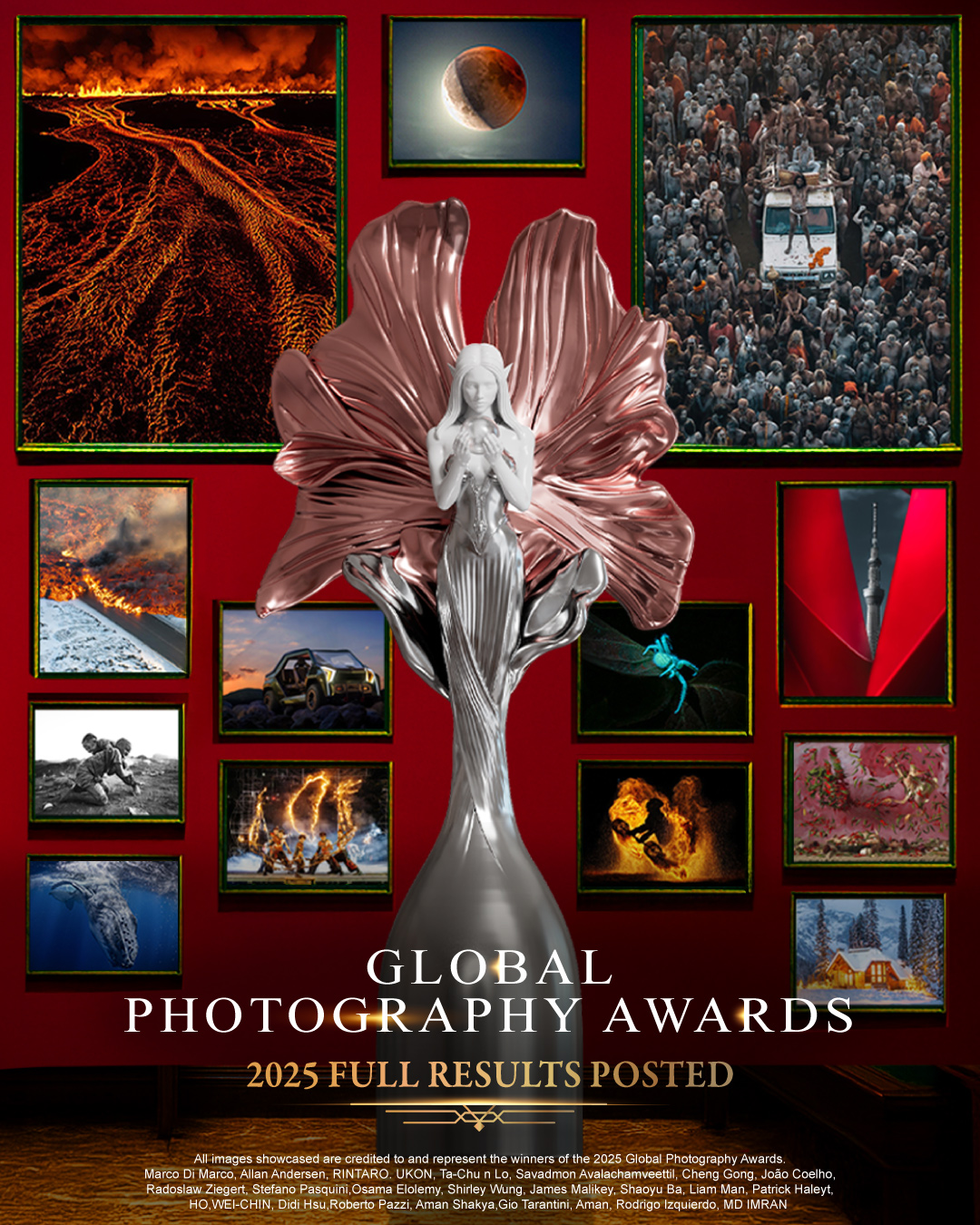

Winning Entries

Explore more about the Unscripted & Unseen: Yuki Hayashi’s Commitment to Real Moments here.

ADVERTISEMENT