1Please give us a brief bio of yourself and your design background.

I'm Jiageng Guo. I’m a Chinese-born architectural designer from Xinjiang who is now based in NYC. My work is driven by interwoven programs, urban landscapes, and associated material cultures. I use multimedia research and a collaborative process to rethink how architecture connects to the city.

2What made you become/why did you choose to become a designer/artist?

Growing up in a culturally diverse environment sparked my interest in how architecture can foster collective agency and cultural exchange. I’ve always been fascinated by how spaces shape and reflect people’s experiences, which led me to create architecture that enriches city life through the interplay of programming and urban landscapes.

3Tell us more about your agency/company, job profile, and what you do.

I am currently contributing to the SPARC Kips Bay project in NYC at Dattner Architects—a mission-driven firm that views architecture as social infrastructure, enriching the urban environment. Before this, I worked at Buro Ole Scheeren, exploring large-scale, forward-thinking concepts, and at Junya Ishigami, where I learned about unconventional spatial constructs and the phenomenological creation of architecture as an expanded landscape. These experiences continue to shape my collaborative, holistic approach to design.

4What does “design” mean to you?

For me, design is a vessel for cultural exchange. It should be contextual—enhancing its surroundings—while being programmatic, functional, and responsive to the users’ needs.

5What’s your favorite kind of design and why?

I’m particularly drawn to public architecture, where projects involve multiple stakeholders therefore capitalism does not alone describe demands.

6To you, what makes a “good” design?

A “good” design is a holistic blend of context, program, creativity, and sustainability—an interplay that balances function with a sense of place and spirit.

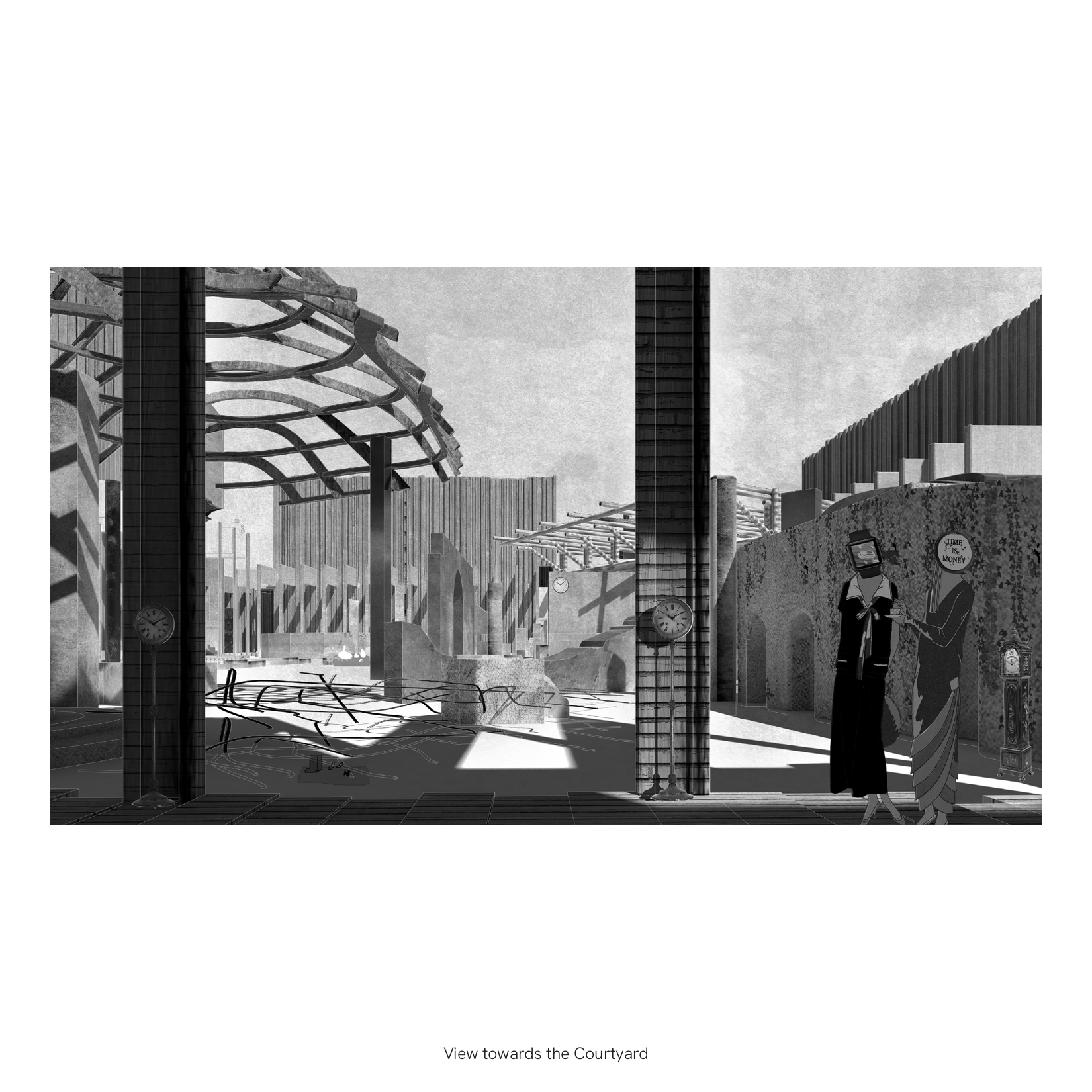

7How did you come up with the idea for your award-winning design?

“Mechanical Time and Body Time” arose from observing how our lives are structured by both mechanical systems (clocks, schedules) and our internal, bodily rhythms (sleep cycles, instincts). I wanted to merge these often-conflicting senses of time into a single spatial narrative—one that brings people together and highlights our shared, yet dual, experience of time.

8What was your main source of inspiration for this design?

Alan Lightman’s novel Einstein’s Dreams provided the central spark. It explores mechanical time versus body time, a duality that deeply resonated with the concept I wanted to realise architecturally.

9Do you think your country and its cultural heritage has an impact on your design process?

Absolutely. Xinjiang is a melting pot of diverse ethnicities and cultures. These collisions appear in both formal and informal spaces—like bazaars, theaters, alleyways, and underground marketplaces—that naturally foster cultural dialogues. Experiencing such variety has profoundly influenced how I view and approach architecture.

10Congratulations! As the winner of the London Design Awards, what does it mean to you and your company and team to receive this award distinction?

It’s incredibly affirming. This recognition validates my conceptual explorations and underscores the importance of pedagogical thinking in design. It motivates me and my collaborators to keep pushing boundaries—especially in our current political climate—where architecture can serve as a dialogue.

11Can you explain a bit about the winning work you entered into the London Design Awards, and why you chose to enter this project?

"Mechanical Time and Body Time” encapsulates my design philosophy: cultural exchange expressed through program, context, detailing, and lighting. I submitted it because it tackles a universal phenomenon—time—in a divided yet cohesive way, prompting users to reflect on their relationship with time. It felt like the ideal representation of my creative vision on an international stage.

12What were the main challenges you faced during the design process, and how did you overcome them?

One major challenge was translating the abstract concept of time into tangible architectural features. I addressed it by mapping how people move through the space, layering in cyclical design cues, and referencing cultural archetypes—like cloisters for mechanical time and spontaneous, communal structures for body time.

13How do you think winning this award will impact your future as a designer?

It broadens my network, increases visibility, and confirms the value of my experimental approach. This honour encourages me to keep exploring, pushing boundaries, and fostering research-driven, conceptually provocative designs.

14What are your top three (3) favorite things about the design industry?

1. Collaboration: The best projects draw on diverse perspectives and disciplines.

2. Associations: Seemingly unrelated elements often reveal unexpected connections during the design process.

3. Creative Storytelling: Every design narrates a story of culture, environment, and human experience.

15What sets your design apart from others in the same category?

I strive to bridge the tangible and intangible—turning concepts like cyclical time and subjective perception into built environments that engage both mind and body. Merging function, poetic narrative, and user experience helps my work stand out.

16Where do you see the evolution of design industry going over the next 5-10 years?

I foresee a move toward immersive, tech-enhanced, and sustainable solutions, with designers leveraging AI and virtual reality for rapid prototyping and conceptual exploration. Environmental responsibility and wellness-centric approaches will likely become even more integral.

17What advice do you have for aspiring designers who want to create award-winning designs?

• Stay Curious: Keep learning and experimenting beyond your immediate field.

• Develop Your Voice: Cultivate a unique angle or conceptual anchor.

• Iterate and Refine: Design is iterative—continuously test and sharpen your ideas.

18What resources would you recommend to someone who wants to improve their skills in the design industry?

• Observation of Everyday Life: Examine mundane routines or objects; they can reveal surprisingly rich design insights.

• Community & Mentorship: Engage in local meetups or online forums (e.g., Behance, Dribble, Architizer) to share and critique work.

• Design Publications & Journals: Stay current via platforms like Architectural Review, Dezeen, and Detail.

19Tell us something you have never told anyone else.

I often weave subtle, hidden motifs into my initial sketches—like personal memories or patterns from nature. They rarely appear in final presentations but keep my creative spirit alive.

20Who has inspired you in your life and why?

1. Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b. 1939): As the first artist-in-residence at NYC’s Department of Sanitation, she used simple yet radical interventions (like mirror-cladding a garbage truck) to completely transform how we perceive everyday urban objects and services.

2. Arne Jacobsen (1902–1971): A pioneer of “total design,” exemplified by his work on the SAS Hotel in Copenhagen. He designed every detail—from the building’s structure to the cutlery—creating a holistic design language that immerses users at every scale.

21What is your key to success? Any parting words of wisdom?

Persistence and openness to feedback are essential. Each critique is an opportunity to refine or pivot an idea. Stay curious, and don’t shy away from uncharted territories—sometimes the most unexpected path leads to the biggest breakthrough.

22Do you have anything else you would like to add to the interview?

I’m grateful to the London Design Awards team for championing conceptual exploration. I hope my work inspires others to transform abstract ideas into architecture that serves communities and sparks meaningful dialogue.